Note: Gunnar Myrdal died in 1987, less than 70 years ago. Therefore, this work is protected by copyright, restricting your legal rights to reproduce it. However, you are welcome to view it on screen, as you do now. Read more about copyright.

Full resolution (TIFF) - On this page / på denna sida - Appendices - 5. A Parallel to the Negro Problem

<< prev. page << föreg. sida << >> nästa sida >> next page >>

Below is the raw OCR text

from the above scanned image.

Do you see an error? Proofread the page now!

Här nedan syns maskintolkade texten från faksimilbilden ovan.

Ser du något fel? Korrekturläs sidan nu!

This page has never been proofread. / Denna sida har aldrig korrekturlästs.

1076 An American Dilemma

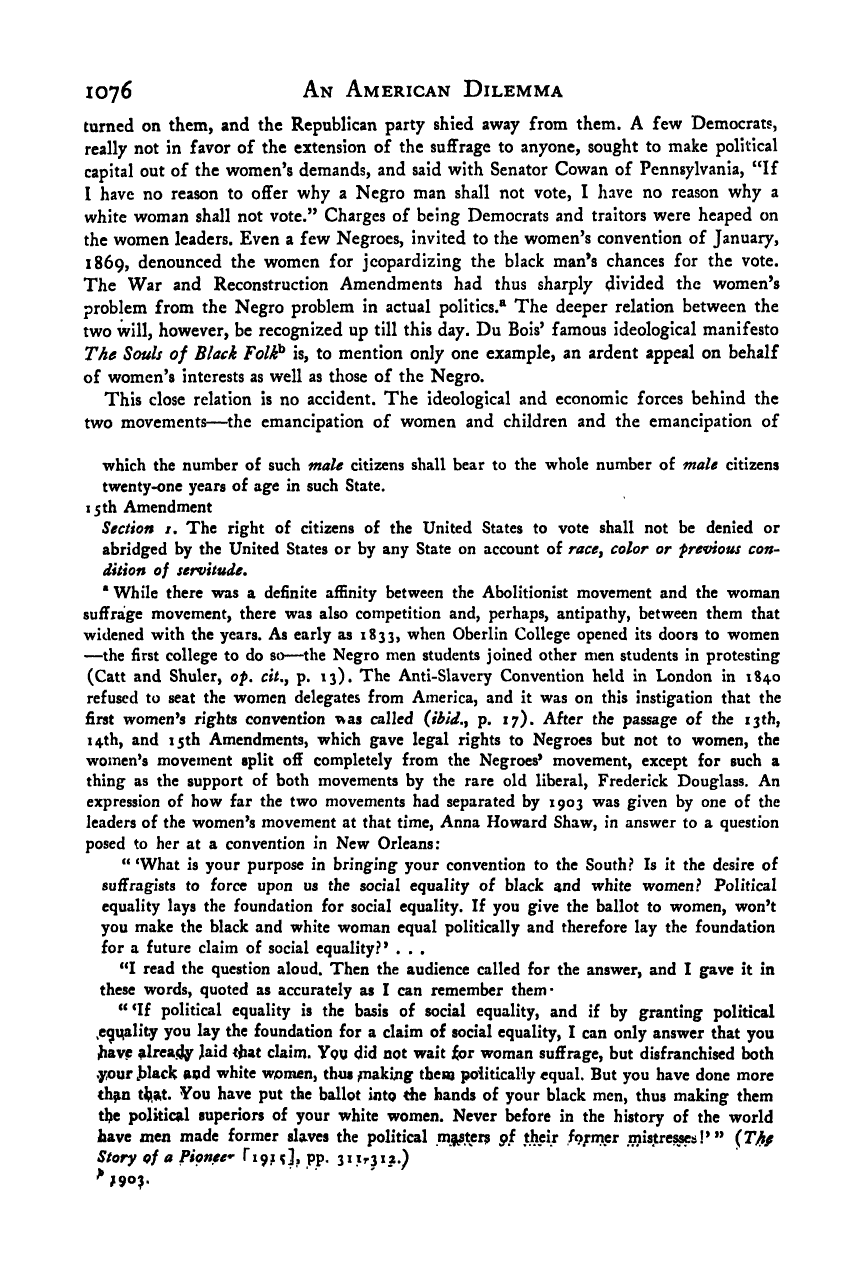

turned on them, and the Republican party shied away from them. A few Democrats,

really not in favor of the extension of the suffrage to anyone, sought to make political

capital out of the women’s demands, and said with Senator Cowan of Pennsylvania, “If

I have no reason to offer why a Negro man shall not vote, I have no reason why a

white woman shall not vote.” Charges of being Democrats and traitors were heaped on

the women leaders. Even a few Negroes, invited to the women’s convention of January,

1869, denounced the women for jeopardizing the black man’s chances for the vote.

The War and Reconstruction Amendments had thus sharply divided the women’s

problem from the Negro problem in actual politics.® The deeper relation between the

two will, however, be recognized up till this day. Du Bois’ famous ideological manifesto

The Souls of Black Follf^ is, to mention only one example, an ardent appeal on behalf

of women’s interests as well as those of the Negro.

This close relation is no accident. The ideological and economic forces behind the

two movements—the emancipation of women and children and the emancipation of

which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens

twenty-one years of age in such State.

15 th Amendment

Section /. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or

abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color or frevious con-‘

dition of servitude^

* While there was a definite affinity between the Abolitionist movement and the woman

suffrage movement, there was also competition and, perhaps, antipathy, between them that

widened with the years. As early as 1833, when Oberlin College opened its doors to women

—the first college to do so—the Negro men students joined other men students in protesting

(Catt and Shuler, o/>. «/., p. 13), The Anti-Slavery Convention held in London in 1S40

refused to seat the women delegates from America, and it was on this instigation that the

first women’s rights convention T\as called (fhJd.y p. 17). After the passage of the 13th,

14th, and 15th Amendments, which gave legal rights to Negroes but not to women, the

women’s movement split off completely from the Negroes’ movement, except for such a

thing as the support of both movements by the rare old liberal, Frederick Douglass. An

expression of how far the two movements had separated by 1903 was given by one of the

leaders of the women’s movement at that time, Anna Howard Shaw, in answer to a question

posed to her at a convention in New Orleans;

“ What is your purpose in bringing your convention to the South? Is it the desire of

suffragists to force upon us the social equality of black and white women? Political

equality lays the foundation for social equality. If you give the ballot to women, won’t

you make the black and white woman equal politically and therefore lay the foundation

for a future claim of social equality?’ . . .

“I read the question aloud. Then the audience called for the answer, and I gave it in

these words, quoted as accurately as I can remember them*

“‘If political equality is the basis of social equality, and if by granting political

.e^i^ality you lay the foundation for a claim of social equality, I can only answer that you

have already Jaid that claim. Yqu did not wait for woman suffrage, but disfranchised both

your Jblack and white women, thus yaking them politically equal. But you have done more

th^n that. You have put the ballot into the hands of your black men, thus making them

the political superiors of your white women. Never before in the history of the world

have men made former slaves the political meters pf their former .mistress!”’ (Tfy

Story of a Pioneer ^19^5], pp, 3ixr3X2.)

<< prev. page << föreg. sida << >> nästa sida >> next page >>